Iron

![Main pit at the Sunrise Iron Mine near Hartville. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland, WSGS] Sunrise Iron Mine](../images/minerals/sunrise-mine.jpg)

The WSGS completed its investigation into the iron

resources of Wyoming in 2015 with the publication of its Report of Investigations No. 67.

The goal of the study was to consolidate and correct information on iron from a wide variety

of earlier investigations, the latest of which was published by the U.S. Bureau of Mines in

1976. WSGS RI-67 not only fulfills that goal, but also provides better perspective on iron resources

throughout Wyoming along with new site information and multi-element analyses that were previously

absent or incomplete.

![Iron concretion in the Thermopolis Shale south of Laramie. These concretions have been used as a weighting factor in cement. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland] Iron concretion](../images/minerals/thermopolis-shale.jpg)

Iron has been a significant resource in the history of Wyoming, providing raw material, jobs,

and economic development. The earliest iron mining and use was by Paleo-Indians in the Sunrise

area, in southeast Wyoming for iron oxide pigment between 8,000 and 13,000 years ago. In the late 1800s, Wyoming

produced concretionary hematite from the Rawlins area for use as paint pigment and smelting flux.

Titaniferous magnetite, identified prior to 1850, has been mined sporadically from magmatic

segregation deposits in the Iron Mountain area for use as a weighting additive in cement.

Archean banded iron formation (BIF) mined in both the Hartville Uplift, between 1899 and 1980, and near South Pass,

from 1962 to 1983, accounted for more than 132 million tons of iron ore, shipped out of state

for iron and steel manufacture. Over time, numerous smaller deposits across the state have also

been investigated as potential sources of iron.

Wyoming currently has no active iron mines but does have in-place iron ore

resources that may have future economic viability. For example, iron deposits

at South Pass and in the Hartville Uplift have not been mined out and still

contain large amounts of iron ore. Numerous

small iron occurrences are known across Wyoming, and recent exploration has identified at least

one potentially large and previously unknown deposit in the Rattlesnake Hills-Granite Mountain area in central Wyoming.

All known iron occurrences from various resources have been compiled and summarized in

sections of WSGS RI-67. Analytical data is presented within the text of the report, and

complete analyses are included in the appendix.

Elemental iron is the fourth most abundant element in the earth’s crust at about 5 percent

and is most commonly found combined with oxygen in the form of iron oxide minerals, particularly

magnetite and hematite. The demand for iron fluctuates as second and third world

countries urbanize and continue developing. Iron will likely always remain a necessity for everyday life

on a global scale. It is integral to products that range from paperclips and metal alloys to

cosmetics, fertilizer, and animal feed. A wide variety of uses for iron is shown in the following table:

Uses for Iron

|

Iron (III) Acetate |

dyes, mordants |

|

Iron Arsenate |

pesticides |

|

Iron (III) Chloride |

sewage treatment, dyes, animal feed additive, electronic etching, catalyst |

|

Iron Hydroxide |

water purification systems |

|

Iron (III) Phosphate |

molluscicides, corrosion resistance/rustproofing, adhesive, battery electrodes |

|

Iron (II & III) Sulfate |

dyes/stains, black ink, treatment of anemia, sewage and water treatment, reducing agent,

fertilizer, herbicide, food fortification, preservation of wood paneling |

|

Cast Iron |

frying pans, griddles, skillets, Dutch ovens, waffle irons, pipes, auto parts, building

construction, slurry pumps, ball mills, pulverizers |

Metallic Iron |

permanent and electro magnets |

|

Stainless Steel |

cutlery, surgical instruments, cookware, appliances, architecture, sculptures, railcars,

automotive bodies, fibers, guns, watches |

|

Steel |

pipes, construction, heavy equipment, furniture, steel wool, tools, armor, bolts, nails,

screws, appliances, wire, railroad tracks, reinforcing mesh/bars, automobiles, trains, ships, magnetic cores |

|

Wrought Iron |

fences, furniture, home decor |

|

Miscellaneous |

coal washing, drilling mud/high density slurries, abrasives/polishing compounds,

thermite/welding, magnetic tape and recordings, filtration, photocatalyst, calamine lotion ingredient |

Gold in Wyoming

![Gold coins were in common use during the late 1800s and the early 1900s. [Credit: Wayne Sutherland, WSGS] Gold coins.](../images/minerals/gold-coins.jpg)

Gold, the intrinsically valuable "royal metal," derives its value from the combination of its rarity and beauty along with its softness (2.5 to 3 on the mohs hardness scale), malleability,

ductility, ease of alloying with other metals such as copper and silver, and its high resistance to corrosion and tarnish. Various estimates place the average gold

content of the earth’s crust around 3.1 parts per billion (ppb), or roughly 0.0001 ounce/ton. Although disseminated gold is widely distributed, concentrations greater than

0.5 ppm, or 0.5 g/tonne, are near minimum for economic recovery in a modern low-grade, large-tonnage gold mine. Higher grades are always desirable and are usually necessary

to initiate mining prior to recovery of the lowest grade material.

Gold has a specific gravity of 19.3 – much heavier than the specific gravity of quartz (2.65), a common host rock for gold. Other host rocks may be heavier than

quartz, but even the heaviest, such as banded iron formation, have specific gravities less than half that of gold. The great difference in weight between gold and

its host rocks allows it to concentrate in placer deposits from which it can easily be recovered. Since earliest times, gold has been used for both objects of art

and for coinage.

Gold and other metals have been mined from primary deposits in Precambrian rocks exposed in the cores of Wyoming’s mountain uplifts and in some Tertiary volcanic and

intrusive rocks. Gold has also been mined from placer deposits concentrated by weathering and erosion of those primary occurrences.

History

![Mary Ellen mine in the South Pass-Atlantic City district, 1989. [Credit: Wayne Sutherland, WSGS] Bentonite-plant](../images/minerals/mary-ellen-mine.jpg) Around 1842, travelers along the old emigrant trail (part of the Oregon Trail) first reported placer gold near the Sweetwater River in the area now known as the Lewiston district, near

the southern tip of the Wind River Range (see Principal Metal District Map). Indian hostilities prevented serious prospecting until the 1860s. Wyoming’s first gold rush sprang from the 1867 discovery of

bedrock-hosted gold west of the Lewiston district in what became the famous Carissa lode.

Around 1842, travelers along the old emigrant trail (part of the Oregon Trail) first reported placer gold near the Sweetwater River in the area now known as the Lewiston district, near

the southern tip of the Wind River Range (see Principal Metal District Map). Indian hostilities prevented serious prospecting until the 1860s. Wyoming’s first gold rush sprang from the 1867 discovery of

bedrock-hosted gold west of the Lewiston district in what became the famous Carissa lode.

In 1869, the settlements of South Pass, Atlantic City, and Miners Delight boasted a combined population of more than 2,500. Gold production from the Carissa totaled between

50,000 and 180,000 ounces before 1911. Total production from Wyoming is unknown because no records were kept, and few estimates were made before about 1900.

Mining districts were organized in several locations across Wyoming during the late 1860s and 1870s. The South Pass-Atlantic City district was first and foremost.

Other districts discovered during that era of relatively high gold prices included Lewiston (about 12 miles southeast of the South Pass-Atlantic City district); Centennial

Ridge, Douglas Creek, Gold Hill, Keystone, and New Rambler (all in the Medicine Bow Mountains); Seminoe Mountains; Copper Mountain in the Owl Creek Mountains; and Mineral Hill

in the Black Hills. Recent gold exploration activity in Wyoming has emphasized both historic mining districts as well as newer discoveries.

Wyoming gold districts are included within the principal metal districts and mineralized areas (see Principal Metal District Map) but may represent more detailed subdivisions. These gold districts

are discussed under headings of some of Wyoming’s mountain ranges, including Wind River Range, Medicine Bow Mountains and Sierra Madre, Absaroka Mountains, Laramie Mountains, Rattlesnake Hills, and

the Bear Lodge Mountains (see separate tabs on this page).

The dramatic rise of gold prices beginning in 2005 led to renewed interest in Wyoming gold. Individual prospectors, recreationists, and a few major

companies have recently explored historic gold districts and potential new deposits.

Precious Metal Purity

|

Fineness and Karats |

Percent Gold |

|

999, 24 |

99.9% |

|

990, 23.8 |

99% |

|

916.67, 22 |

91.6% |

|

900, 21.6 |

90% |

|

875, 21 |

87.5% |

|

833, 20 |

83.3% |

750, 18 |

75% |

|

583.30, 14 |

58.3% |

|

500, 12 |

50% |

|

416.67, 10 |

41.7% |

Fineness refers to the purity of precious metal contained in an alloy as parts per thousand.

A purity of 99.9% precious metal is 999 fine, which may be written in decimal form as .999 fine.

A precious metal containing 10 percent other metals is said to be 900 fine or to have a fineness of 900.

Purity of a gold (or platinum) alloy may also be stated in karats. One karat is 1/24 part by weight of the total mass;

pure gold (999 fine to 1000 fine) is 24-karat gold. 18-karat gold is an alloy of 75% gold or 750 fine. The spelling "carats"

is used outside of the United States and Canada and should not be confused with the carat weight used for gemstones. A karat

designation of purity is accompanied by the abbreviation K (or ct).

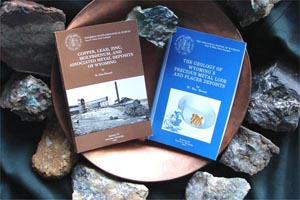

Old mines are often a good place to begin prospecting. Information on most of Wyoming’s gold and precious metals deposits can be found in the following recommended publications

by the Wyoming State Geological Survey:

Hausel, W.D., 1989, The geology of Wyoming’s precious metal lode and placer deposits: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] WSGS Bulletin 68, 248 p., 6 pls.

Hausel, W.D., 2002, Searching for gold in Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Information Pamphlet 9, 12 p.

Additional references relating to gold and other metals in Wyoming are found on the References Page.

Southern Wind River Range

![Gold-bearing shear zone at the Carissa gold mine. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland, WSGS] Mine](../images/minerals/gold-bearing-shear-zone.jpg)

![Placer operation in the Oregon Buttes-Dickie Springs paleoplacers in 2004. [Credit: W. Dan Hausel, WSGS] Mine](../images/minerals/placer-operation.jpg)

The historic South Pass-Atlantic City and Lewiston districts are characterized by abundant small lode and placer deposits with additional potential for large-tonnage, low-grade mineralization and

small undiscovered high-grade deposits. This area is a greenstone belt that forms a synclinorium of metamorphosed sedimentary, volcanic, and plutonic rocks intruded by granitic plutons. Gold

mineralization occurs mainly in foliation-parallel shear zones and is associated with quartz, sulfides, carbonates, and related wallrock alterations. An estimate by Hausel (1989) suggests that as

much as 334,000 ounces of gold were mined from the South Pass-Atlantic City district.

Placer and paleoplacer gold deposits are widespread in the vicinity of the greenstone belt. The Oregon Buttes-Dickie Springs paleoplacers are a few miles south of the South

Pass-Atlantic City district. Love, Antweiller, and Mosier (1978) described these paleoplacers as hosting as much as 28.5 million ounces of placer gold.

Medicine Bow Mountains and Sierra Madre

![Queen mine on Centennial Ridge. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland, WSGS] Mine](../images/minerals/queen-mine.jpg)

The Medicine Bow Mountains and Sierra Madre are Precambrian-cored Laramide uplifts that straddle the margin of the Wyoming craton.

The Wyoming craton was established more than approximately 2.7 billion years ago (2.7 Ga, or Giga-annum), but was later affected by a

regional metamorphic event 1.9–1.7 Ga. The south boundary of the Wyoming Craton in the Medicine Bow Mountains and Sierra Madre

terminates against the Mullen Creek-Nash Fork shear zone. This shear zone, which forms part of the Cheyenne belt suture, represents a

continental-arc collision zone separating the Wyoming Province to the north from cratonized (1.7 Ga) Proterozoic basement of the Colorado

Province to the south.

Within the Colorado Province south of the Cheyenne belt, metavolcanic and metasedimentary rocks provide excellent hosts for magmatic

massive sulfide mineralization (copper, zinc, lead, silver, gold) and some shear zone copper, gold, and associated gold placers. Layered

mafic-ultramafic intrusives, ultramafic massifs, and fragments with platinum, palladium, gold, silver, copper, titanium, chromium, and

vanadium anomalies occur within the Proterozoic terrain – most notable are the Mullen Creek, Lake Owen, and Puzzler Hill complexes. The

New Rambler mine is located along the northeastern edge of the Mullen Creek mafic-ultramafic complex in the Medicine Bow Mountains and is

Wyoming’s only mine known to have historically produced platinum and palladium. The mineralization, occurring in hydrothermally altered mafic shear-zone

cataclastics, may have been remobilized from the layered complex. Because of their high potential for platinum-palladium mineralization,

Mullen Creek, Lake Owen to the east, and Puzzler Hill in the Sierra Madre continue to be platinum exploration targets.

North of the Cheyenne belt in the Medicine Bows and Sierra Madre, the Wyoming Province includes amphibolite-grade schists and gneisses

overlain by younger Archean and Proterozoic metasedimentary and metaigneous rocks. Metaconglomerates found in several of the Precambrian

units are considered potential sources for uranium, thorium, and rare earth elements. Similarities between these rocks and the gold-rich

quartz-pebble metaconglomerates of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, suggest that they also have potential to host significant

copper, gold, and silver mineralization.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, intense prospecting left numerous remnants of mines and prospects concentrated in the broad region

underlain by sheared rocks of the Cheyenne belt, although scattered mineralization occurs throughout both mountain ranges. There is no

evidence that any of the significant historical mines, with the exception of the Centennial mine, were ever mined out. Mine operations

usually ceased due to factors such as declining metal prices, lack of technological developments, ore complexity below the zone of oxidation, outbreak of war, and other

political or human-related factors. The Centennial mine ceased operations because the mineralized lode was offset by faulting. The

extension of the ore deposit was never found.

Centennial Ridge District

Placer gold, discovered in gravels along the Middle Fork of the Little Laramie River, led to the organization of the Centennial

Ridge mining district in the east-central Medicine Bow Mountains in 1876. Placer activity was followed by several lode discoveries

including the Centennial mine. A new wave of prospecting and development followed the 1901 discovery of platinum associated with copper

ores at the New Rambler mine 5 miles to the southwest. Structural fabric within the district is generally northeast-trending and parallel

to the Cheyenne belt. Lode mineralization includes foliation/schistosity parallel gold-bearing quartz veins in biotite and hornblende

gneisses and schists, and gold-platinum fracture-filling and replacement veins in shear zones and faults cutting the gneisses and schists.

Sulfides and arsenides accompany gold-platinum in the fracture fillings. Sulfide-rich zones, dominated by pyrite and occurring in mafic host

rocks, usually accompany the richest ores in the district. Actual production from the Centennial Ridge district is unknown. However, the

Centennial mine produced an estimated 4,500 ounces of gold.

Douglas Creek District

![Douglas Creek placer gold, donated to the WSGS by Paul Allred. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland, WSGS] placer gold](../images/minerals/douglas-creek-placer-gold.jpg) The Douglas Creek district in the central Medicine Bow Mountains includes all placer deposits along Douglas Creek and its tributaries, from Rob Roy Reservoir southward for 6

miles to below Lake Creek. Gold was discovered in Moore’s Gulch, a tributary of Douglas Creek, by Iram Moore in 1868. Lode gold discoveries in both the New Rambler and

Keystone districts resulted from placer gold being traced upstream to its primary sources. Heavy placer activity along the creek included elaborate hydraulic ditches in use by

1876. Resurgent placer activities during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s used gasoline-powered draglines and floating washing plants. Gold recovered from gravels up to 20 feet thick

varied from 890 to 960 fine, with some silver and traces of platinum. Currey (1965) estimated total gold production from the Douglas Creek placers at about 4,000 ounces. The

Douglas Creek district remains a popular area for amateur placer mining.

The Douglas Creek district in the central Medicine Bow Mountains includes all placer deposits along Douglas Creek and its tributaries, from Rob Roy Reservoir southward for 6

miles to below Lake Creek. Gold was discovered in Moore’s Gulch, a tributary of Douglas Creek, by Iram Moore in 1868. Lode gold discoveries in both the New Rambler and

Keystone districts resulted from placer gold being traced upstream to its primary sources. Heavy placer activity along the creek included elaborate hydraulic ditches in use by

1876. Resurgent placer activities during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s used gasoline-powered draglines and floating washing plants. Gold recovered from gravels up to 20 feet thick

varied from 890 to 960 fine, with some silver and traces of platinum. Currey (1965) estimated total gold production from the Douglas Creek placers at about 4,000 ounces. The

Douglas Creek district remains a popular area for amateur placer mining.

New Rambler District

The New Rambler district, just west of Douglas Creek, is near the south edge of the

Cheyenne belt along the Rambler shear zone, an east-trending branch of the Mullen Creek-Nash

Fork shear zone. The Rambler shear zone, numerous local northeast-trending shears, and a few

northwest-trending faults cut foliated granodiorite, the younger Rambler Granite, and the distorted

northeast extremities of the Mullen Creek mafic-ultramafic complex.

Primary copper sulfides and gold occur in quartz veins, as fracture fillings, and in zones of brecciation.

Significant secondary mineralization, found only in the New Rambler mine, often

assayed more than 35 percent copper. The New Rambler mine first opened as a gold mine in 1870.

Copper was discovered in 1900 at a depth of 65 feet, and platinum within the covellite ore was

discovered in 1901. Estimated production from the New Rambler mine totaled 171.3 ounces of gold,

7,346 ounces of silver, 1,753,924 pounds of copper, 910 ounces of platinum, and 16,870 ounces of

palladium. The New Rambler area is considered an attractive target for platinum group metals

exploration.

Keystone District

![Independence mine shaft, Keystone district, in 2002. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland, WSGS] Keystone district](../images/minerals/keystone-district.jpg) The Keystone district, about 3 miles southeast of the New Rambler district, hosts lode gold

mineralization concentrated along northwest-trending shears that cut quartz diorite, quartz-biotite

schist, and foliated granodiorite. These shears, subsidiary to the Mullen Creek-Nash Fork shear

zone, provide loci for quartz veins and veinlets and copper-gold mineralization with associated

epidotization of wallrock. Currey (1965) estimated the total lode gold production from the mines

in the Keystone district at about 8,500 ounces.

The Keystone district, about 3 miles southeast of the New Rambler district, hosts lode gold

mineralization concentrated along northwest-trending shears that cut quartz diorite, quartz-biotite

schist, and foliated granodiorite. These shears, subsidiary to the Mullen Creek-Nash Fork shear

zone, provide loci for quartz veins and veinlets and copper-gold mineralization with associated

epidotization of wallrock. Currey (1965) estimated the total lode gold production from the mines

in the Keystone district at about 8,500 ounces.

Sierra Madre / Encampment District

The Encampment mining district in the Sierra Madre mainly produced copper after its discovery in

1874. However, gold and silver were significant byproducts of copper mining. The Encampment

(also known as the Grand Encampment) district includes the entire Sierra Madre in south-central

Wyoming and extends into Colorado. The district is bisected by the generally east-trending Mullen

Creek-Nash Fork shear zone, which is more than one-half mile wide in places. This shear zone forms

part of the Cheyenne belt suture (see Principal Metal Districts Map above) that separates the Archean

Wyoming Province to the north from cratonized Proterozoic basement of the Colorado Province to

the south.

![Large prospect in the Sierra Madre with extensive copper staining. [Credit: Liz Cola] prospect in the Sierra Madre](../images/minerals/sierra-madre-prospect.jpg) Thick successions of Late Proterozoic metasediments that overlie the Archean basement characterize

the northern part of the district, where mineralization is typified by copper-bearing quartzites,

pegmatites, quartz veins, and unaniferous metaconglomerate. Middle Proterozoic calc-alkaline

metavolcanics intruded by granitic plutons characterize the southern part of the district, where

rocks host stratiform volcanogenic sulfides and related mineralization. Fracture-controlled,

copper-dominated base metal deposits typify mineralization within the shear zone.

Thick successions of Late Proterozoic metasediments that overlie the Archean basement characterize

the northern part of the district, where mineralization is typified by copper-bearing quartzites,

pegmatites, quartz veins, and unaniferous metaconglomerate. Middle Proterozoic calc-alkaline

metavolcanics intruded by granitic plutons characterize the southern part of the district, where

rocks host stratiform volcanogenic sulfides and related mineralization. Fracture-controlled,

copper-dominated base metal deposits typify mineralization within the shear zone.

The Ferris-Haggarty mine in the central Sierra Madre was one of the world’s more important

copper deposits during the early 1900s. This significant deposit with accessory gold and some

silver was developed in a sheared metaconglomerate. The mine produced an estimated 21 million

pounds of copper with some byproduct gold and silver. A 1988 estimate of unmined ore included

928,500 tons of 6.5 percent copper containing 116,800 ounces of gold. Current high metals prices

have sparked re-evaluation and exploration of the Ferris-Haggarty and adjacent areas.

Amateur prospectors still search the Sierra Madre for gold although it was always secondary to

copper in the Encampment district.

Absaroka Mountains

Several large Eocene volcanic centers in the Absaroka Mountains of northwestern Wyoming host

significant porphyry copper-silver along with some associated gold. Mining districts in the

Absarokas include Kirwin, Stinking Water, Sunlight, and New World (Cook City). Veins associated

with the porphyries were first worked in the late 1800s. Large-tonnage, low-grade polymetallic

porphyry deposits include disseminated, stockwork, and vein mineralization accompanied by

hydrothermal alteration halos. The volcanic centers also exhibit some supergene enriched

deposits, replacement deposits within Paleozoic carbonates (in the New World district), and

related downstream gold placers. Historically, these placers had little economic importance,

however, amateur prospectors continue to work some of them today.

Laramie Mountains

The Silver Crown district, located on the east flank of the Laramie Mountains in southeast Wyoming,

was organized in 1879. A mill and smelter operated on a small scale in the district from 1880 to

1900. Structurally controlled copper-gold mineralization parallels regional foliation or occurs

in tensional fractures. In the northern part of the district, narrow clay-filled shear zone

cataclastics and mylonites host massive, white, copper-bearing quartz veins, and lenses.

These are generally excessively narrow with limited tonnage. The southern part of the district

hosts low-grade, large-tonnage disseminated copper-gold within granodiorite and quartz monzonite.

![2016 airborne geophysical surveying in the Rattlesnake Hills. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland] geophysical surveying](../images/minerals/geophysical-surveying.jpg)

Rattlesnake Hills

The Rattlesnake Hills in central Wyoming are a partially exposed fragment of a synformal

Archean greenstone belt that was intruded during the Tertiary by alkalic volcanic rocks.

In 1982, the WSGS discovered anomalous gold in the Rattlesnake Hills in pyrite-rich metachert.

Hausel (1996) recognized a minimum of three episodes of gold mineralization, including

syngenetic stratabound exhalative mineralization, epigenetic mineralization, and disseminated

epithermal gold associated with Tertiary volcanic activity.

![Core drilling in the Rattlesnake Hills, 2009. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland] placer gold](../images/minerals/rattlesnake-hills.jpg)

Exploration in the area by several

companies between 1983 and 1993 suggested a large amount of disseminated low-grade gold

thought to be more than one million ounces. Exploration also identified some higher-grade

stratabound mineralization along with nearby unevaluated targets.

Exploration in the area accelerated after 2008, with efforts by several companies active in the area.

The largest, Evolving Gold Corporation, eventually drilled and evaluated 252,000 ft (76,800 m)

of core, finding significant gold mineralization.

Evolving Gold sold its property in

summer 2015 to GFG Resources Inc., completing the sale in 2016. Exploration activity for

gold in the Rattlesnake Hills by GFG Resources continued with an extensive airborne geophysical survey in 2016 and successful drill programs in 2016

and 2017. Exploration activities by GFG Resources are described on their website.

![Extensive drilling and trenching in the Bear Lodge Mountains contributed to the delineation of significant REE and gold mineralization. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland, WSGS] Bear Lodge](../images/minerals/bear-lodge-trench.jpg)

![Extensive drilling and trenching in the Bear Lodge Mountains contributed to the delineation of significant REE and gold mineralization. [Credit: Wayne M. Sutherland, WSGS] Bear Lodge](../images/minerals/bear-lodge-drilling.jpg)

Bear Lodge Mountains District

The Bear Lodge Mountains district in northeastern Wyoming was first prospected in 1875 after

the discovery of gold in feldspar porphyry near Warren Peak. Recent exploration in the area has

been fostered by both historically known mineralization and by similarities this Tertiary

intrusive complex shares with the 30 Ma gold-hosting Cripple Creek igneous complex in Colorado.

In addition to gold, mineral values in the Bear Lodge have included rare earth elements (REE),

barium, copper, lead, zinc, manganese, niobium, tantalum, thorium, fluorine, and phosphate.

Mineralization in the Bear Lodge Mountains includes disseminated, vein, carbonatite, and

replacement deposits. The greatest potential for resource development are the REE followed by gold.

Rare Element Resources in October 2014 reported an NI 43-101-compliant (*see footnote on Laramie Mtns page) total high-grade

Measured and Indicated (M&I) mineral resource of 15.7 million tonnes (17.3 million tons) averaging

3.11 percent total rare earth oxides at a 1.5 percent cutoff grade, which included M&I resources of

5.4 million tonnes (6 million tons) grading 4.51 percent rare earth oxides at 3 percent cutoff

grade.

Gold mineralization occurs within the same large alkaline-igneous complex as the REE

mineralization and is comingled with REE in places. On March 15, 2011, Rare Element Resources

released an NI 43-101-compliant inferred mineral resource estimate of 26,850 kg

(947,000 oz) of gold contained in 69.3 million tonnes (76.4 million tons) averaging 0.42 ppm

(0.42 g/tonne; 0.122 oz/ton) using a 0.15 ppm (0.15 g/tonne; 0.004 oz/ton) cutoff grade.

Selected References Related to Metals in Wyoming

Publications relating to metals in Wyoming can be downloaded or purchased from the WSGS Publications Sales

and Free Downloads minerals – metals category of the online catalog and from the WSGS Sales

Geologic Mapping page.

Blackstone, D.L. Jr., 1988, Traveler’s guide to the geology of Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological

Survey Bulletin 67, 130 p.

Blackstone, D.L. Jr., and Hausel, W.D., 1992, Field guide to the Seminoe Mountains: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Reprint 48, 10 p. (Reprint 1991, Wyoming Geological Association.)

Currey, D.R., 1965, The Keystone gold-copper prospect area, Albany County, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Preliminary Report 3, 12 p., 1 pl.

Eggler, D.H., Meen, J.K., Welt, F., Dudas, F.O., Furlong, K.P., McCallum, M.E., and Carlson, R.W., 1988, Tectonomagmatism of the Wyoming Province: Colorado School of Mines Quarterly, p. 25–40.

Gersic, J., Peterson, E.K., and Schreiner, R.A., 1990, Appraisal of selected

mineral resources of the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota and Wyoming:

U.S. Bureau of Mines Open File Report MLA 5-90, 225 p.

Graff, P.J., 1978, Geology of the lower part of the Early Proterozoic Snowy Range Supergroup,

Sierra Madre, Wyoming: Laramie, University of Wyoming, Ph.D. dissertation, 85 p.

Harris, R.E., Hausel, W.D., and Meyer, J.E., 1985, Metallic and industrial

minerals map of Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series 14, scale

1:500,000.

Hausel, W.D., 1982, General geologic setting and mineralization of the porphyry copper deposits, Absaroka volcanic plateau, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Reprint 40, 17 p. (Reprint 1982, Wyoming Geological Association.)

Hausel, W.D., 1982, Ore deposits of Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Preliminary Report 19, 39 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1984, Tour guide to the geology and mining history of the South

Pass gold mining district, Fremont County, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological

Survey Public Information Circular 23, folded pamphlet, scale 1:24,000.

Hausel, W.D., 1986, Mineral deposits of the Encampment mining district, Sierra

Madre, Wyoming-Colorado: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of

Investigations 37, 31 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1989, The geology of Wyoming’s precious metal lode and placer deposits: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Bulletin 68, 248 p., 6 pls.

Hausel, W.D., 1991, Economic geology of the South Pass granite-greenstone belt, southern Wind River Range, western Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Report of Investigations 44, 129 p., 2 pls., scale 1:48,000.

Hausel, W.D., 1992, Form, distribution, and geology of gold, platinum, palladium, and silver in Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Reprint 51, 18 p.

Hausel, W.D., 1994, Mining history and geology of some of Wyoming’s metal and gemstone districts and deposits: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Reprint 56, p. 39–64. (Reprinted 1993, Wyoming Geological Association.)

Hausel, W.D., 1993, Guide to the geology, mining districts and ghost towns of the Medicine Bow Mountains and Snowy Range Scenic Byway: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Public Information Circular 32, 53 p., 2 pls.

Hausel, W.D., 1994, Geology of the Cooper Hill mining district, Medicine Bow Mountains, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations 49, 22 p., 1 pl., scale 1:1111.

Hausel, W.D., 1994, Economic geology of the Seminoe Mountains mining district, Carbon County, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations 50, 31 p., 1 pl., scale 1:24,000.

Hausel, W.D., 1996, Geology and gold mineralization of the Rattlesnake Hills,

Granite Mountains, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of

Investigations 52, 28 p., 1 pl., scale 1:24,000.

Hausel, W.D., 1997, Copper, lead, zinc, molybdenum, and other associated metal deposits of Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Bulletin 70, 229 p., 4 pls.

Hausel, W.D., 2002, Searching for gold in Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Information Pamphlet 9, 12 p.

Hausel, W.D., 2006, Revised geologic map of the Miners Delight quadrangle,

Fremont County, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series 38, scale

1:24,000.

Hausel, W.D., 2007, Revised geologic map of the South Pass City quadrangle,

Fremont County, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series 74, scale

1:24,000.

Hausel, W.D., Edwards, B.R., and Graff, P.J., 1992, Geology and mineralization of the Wyoming Province: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Reprint 52, 12 p. (Reprinted from Preprint 91-72 presented at the 1991 SME Annual Meeting, Denver, Colo., February 25–28, 1991: Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration, Inc. [SME].)

Hausel, W.D., Graff, P.J., and Albert, K.G., 1985, Economic geology of the Copper Mountain supracrustal belt, Owl Creek Mountains, Fremont County, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Report of Investigations 28, 33 p., 3 pls., scale 1:24,000.

Hills, F.A., and Houston, R.S., 1979, Early Proterozoic tectonics of the central

Rocky Mountains, North America: University of Wyoming Contributions to Geology,

v. 17, no. 2, p. 89-109.

Houston, R.S., 1993, Late Archean and Early Proterozoic geology of southeastern

Wyoming in Snoke, A.W., Steidtmann, J.R., and Roberts, S.M., (eds.),

Geology of Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Memoir 5, p.78–116.

Houston, R.S., McCallum, M.E., King, J.S., Ruehr, B.B., Myers, W.G., Orback, C.J., King, J.R., Childers, M.O., Irwin Matus, Currey, D.R., Gries, J.C., Stensrud, H.L., Catanzaro, E.J., Swetnam, M.N., Michalek, D.D., and Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1978, A regional study of Precambrian age in that part of the Medicine Bow Mountains lying in southeastern Wyoming—With a chapter on the relationship between Precambrian and Laramide structure: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Memoir 1, 167 p., 35 pls. (Reprinted from 1968.)

Karlstrom, K.E., and Houston, R.S., 1984, The Cheyenne Belt: Analysis of a

Proterozoic suture in southern Wyoming: Precambrian Research, v. 25, p. 415–446.

Klein, Terry, 1974, Geology and mineral deposits of the Silver Crown Mining District,

Laramie County, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Preliminary Report 14, 27 p.,

scale 1:1,200 and ~ 1:25,344.

Love, J.D., Antweiler, J.C., and Mosier, E.L., 1978, A new look at the origin

and volume of the Dickie Springs-Oregon Gulch placer gold at the south end of

the Wind River Mountains in Boyd, R.G., Olson, G.M., and Boberg, W.W.,

(eds.), Resources of the Wind River Basin: Wyoming Geological Association

Thirtieth Annual Field Conference Guidebook, p. 379-391.

Love, J.D., and Christiansen, A.C., comps., 1985, Geologic map of Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey, 3 sheets, scale 1:500,000. (Re-released 2014, Wyoming State Geological Survey).

McCallum, M.E., 1968, The Centennial Ridge gold-platinum district, Albany County,

Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Preliminary Report 7, 12 p., scale 1:20,000. (Reprinted 1982.)

McCallum, M.E., and Orback, C.J., 1968, The New Rambler copper-gold-platinum district,

Albany and Carbon counties, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Preliminary Report 8, 12 p.,

scale ~1:26,400.

Snoke, A.W., Steidtmann, J.R., and Roberts, S.M., eds., 1993, Geology of Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Memoir 5, 2 v., 937 p., 10 pls.

Sutherland, W.M., 2007, Geologic map of the Sundance 30′ x 60′ quadrangle, Crook and Weston counties,

Wyoming and Lawrence and Pennington counties, South Dakota: Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series

78, 26 p., scale 1:100,000.

Sutherland, W.M., 2008, Geologic map of the Devils Tower 30' x 60' quadrangle,

Crook County, Wyoming, Lawrence and Butte counties, South Dakota, and Carter County, Montana:

Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series 81, 29 p., scale 1:100,000.

Sutherland, W.M., and Cola, E.C., 2015, Iron Resources of Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey

Report of Investigations 67, 92 p.

Sutherland, W.M., and Cola, E.C., 2016, A comprehensive report on rare earth elements in Wyoming:

Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations 71, 137 p.

Sutherland, W.M., and Hausel, W.D., 2003, Geologic Map of the Rattlesnake Hills 30’ x 60’ quadrangle,

Fremont and Natrona Counties, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series 61, 28 p., scale 1:100,000.

Sutherland, W.M., and Hausel, W.D., 2005, Preliminary geologic map of the Saratoga 30′ x 60′ quadrangle:

Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 04-10, 34 p., scale 1:100,000.

Sutherland, W.M., and Hausel, W.D., 2005, Preliminary geologic map of the Keystone quadrangle,

Albany and Carbon counties, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 05-6, 21 p., scale 1:24,000.

Sutherland, W.M., and Hausel, W.D., 2005, Geologic map of the Barlow Gap quadrangle, Natrona County,

Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series 67, scale 1:24,000.

Sutherland, W.M., and Hausel, W.D., 2006, Geologic map of the South Pass 30′ x 60′ quadrangle,

Fremont and Sweetwater counties, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series 70, 23 p., scale 1:100,000.

Sutherland, W.M., and Worman, B.N., 2013, Preliminary geologic map of the Blackjack Ranch quadrangle,

Natrona County, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 13-3, 24 p., scale 1:24,000.

Ver Ploeg, A.J., and Boyd, C.S., 2007, Geologic map of the Laramie 30′ x 60′ quadrangle, Albany and Laramie

counties, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Map Series 77, scale 1:100,000.

Wilson, W.H., 1964, The Kirwin mineralized area, Park County, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Preliminary Report 2, 20 p., 2 pls. [With a 1980 Addendum by the author.]

of the online catalog.