Geologic History of Wyoming

The topographic expression we currently observe across Wyoming evolved over billions of years and resulted from a variety of natural geologic processes acting

internally or externally on the earth’s surface. In addition to the mountain ranges, high plains, and sedimentary basins that span the state, the development

of Wyoming’s vast energy resources and mineral deposits, as well as

potential geologic hazards, can all be attributed to geological processes and structural deformation.

Explore the geologic evolution of Wyoming below to discover the timeline of significant events that shaped the land as well as a brief summary of

the general geology of major uplifts and basins in the state.

Wyoming's Geological Timeline

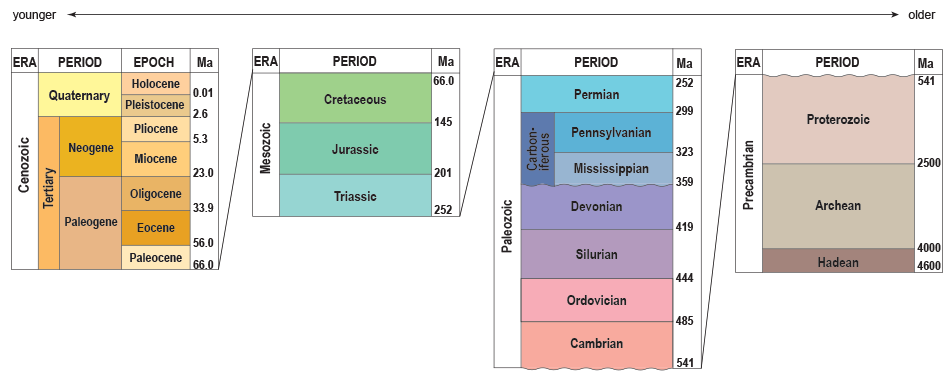

Click on an era below to learn more about the geologic evolution of Wyoming. A geologic time scale is provided below for reference. The "Ma" heading on the time scale

represents the term "mega-annum," which means a period of one million years.

- ►Cenozoic (66 Million years ago to present)

- The Laramide orogeny began in Wyoming in the Late Cretaceous. The peak of deformation occurred during the Paleocene, and the orogenic event was completed by mid-Eocene.

Erosion removed sediments from highlands and deposited them into surrounding basins, which subsided as the mountains rose. A period of volcanic activity occurred during

the Cenozoic, depositing volcaniclastic rocks, flows, intrusive-volcanic bodies, and ash. The entire Rocky Mountain region underwent a period of significant uplift, and the

Pleistocene Ice Age began. Today, there are still earthquakes in the state, suggesting continued crustal movement.

- ►Mesozoic (252–60 million years ago)

- Deposition of red sediments continued throughout the Triassic period. The Jurassic period is marked by minor crustal uplift and transgressive/regressive sequences of the sea.

Marine clay, mud, and sand were deposited, and marine fossils were widely preserved. During the periods when Wyoming was dominated by a continental environment, fluvial systems

deposited clay, silt, and sand. Dinosaurs inhabited the land during the Jurassic and many world-renowned fossil remains have been discovered at sites across the state. In the

Cretaceous, a seaway again covered most of the state. By the end of the Cretaceous, the Sevier orogeny was underway and the Overthrust Belt was developing. The end of the Mesozoic

also marks the extinction of dinosaurs in the geologic record.

- ►Paleozoic (541–252 million years ago)

- Cambrian and Ordovician deposits in Wyoming record subsidence of the land that resulted in westward transgression of the sea and deposition of marine sediments (gravel, sand,

mud, limestone, and dolomite). The Silurian record is not well preserved in Wyoming and likely reflects a period of widespread erosion. Mountain-building events that commenced

in the Pennsylvanian period uplifted the crust and eroded sediments, depositing them into adjacent, low-lying basins where an inland sea still covered the land. In the Permian,

organic-rich marine sediments were deposited in the western seaways while nearshore tidal flat sediments accumulated in the central and eastern parts of the state, resulting in

the thick sequences of red siltstone, shale, gypsum, and sandstones we see today.

- ►Precambrian (4.6 billion years ago to 541 million years ago)

- The Precambrian history in Wyoming is best documented from studies in the Medicine Bow Mountains. Radioactive dating of rocks exposed at the surface indicates two igneous-intrusive

events (2.7 billion years ago and 1.7 billion years ago). Additionally, the Medicine Bow Mountains have a thick metasedimentary cover containing fossilized cyanobacteria (stromatolites) which are as old as 1.7 billion years.

The cyanobacteria are evidence of some of the first known life forms on earth. The Sherman Granite represents a younger Precambrian magmatic igneous-intrusive body and crops out

along U.S. Interstate 80 in the vicinity of the Vedauwoo Recreation Area. Precambrian rocks are also exposed at the core of many uplifts in Wyoming.

Key Mountain-Building Events

Although several orogenic (mountain-building) events have played a role in shaping the geology of state, two main events are most commonly referenced when

considering Wyoming geology, the Sevier and Laramide orogenies. Learn more about these events below.

- ►Sevier Orogeny

- As part of the Cordilleran Thrust Belt, which extends from Mexico to northern Alaska, the Sevier orogeny occurred in Jurassic to Eocene time, approximately 140–50 million years ago

when the Farallon oceanic plate subducted beneath the continental crust of North America near present-day California. Compressive stresses related to collision of the plates resulted

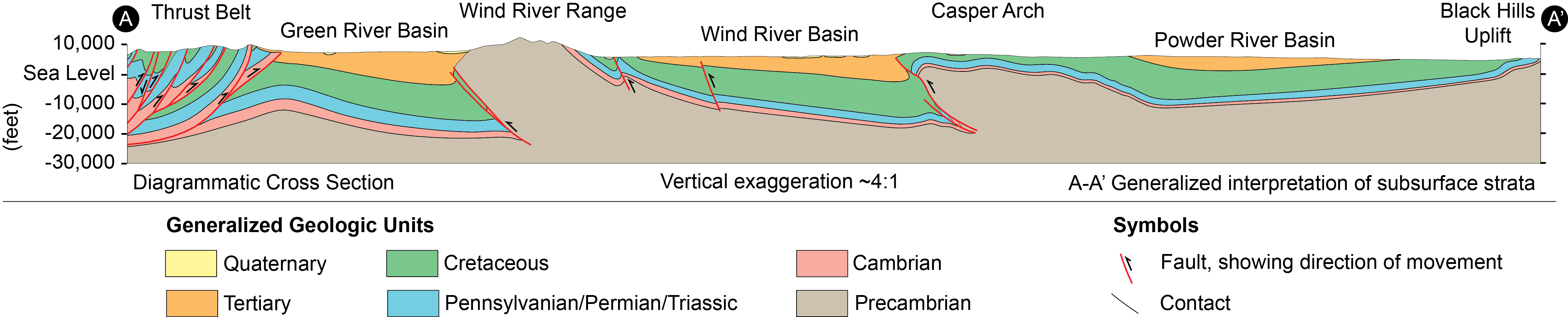

in crustal thickening and mountain building in parts of Nevada, Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming. The north-south trending mountain ranges in western Wyoming are referred to as the Thrust Belt,

the Overthrust Belt, or the fold and thrust belt, and are Sevier structures. Classic Sevier structures are west-dipping, east-vergent thrust faults that displace sedimentary rocks above

the crystalline basement. Because these thrusts do not involve basement rocks, they are referred to as “thin-skinned.” Western Wyoming mountain ranges that comprise the Thrust Belt include

the Snake River, Wyoming, Hoback, Salt River, Tunp, and Sublette ranges.

- ►Laramide Orogeny

- The Laramide orogeny is a significant mountain-building event that occurred synchronously with the Sevier orogeny during the first 20 million years of its duration (70–35 million years ago).

Similar to the Sevier mountain-building event, the Laramide orogeny is thought to be caused by horizontal compression from subduction of the Farallon Plate beneath the North American Plate.

Laramide structures differ from Sevier deformation in that Laramide faults displace crystalline basement rocks as well as sedimentary rocks. This is referred to as “thick-skinned” deformation.

Laramide deformation is unique because it occurred farther inland on the North American Plate rather than at the plate boundary, which is more typical in convergent margin settings. One hypothesis

for inland deformation is that the angle in which the Farallon Plate subducted became shallower, causing crustal thickening in the direction of subduction.

-

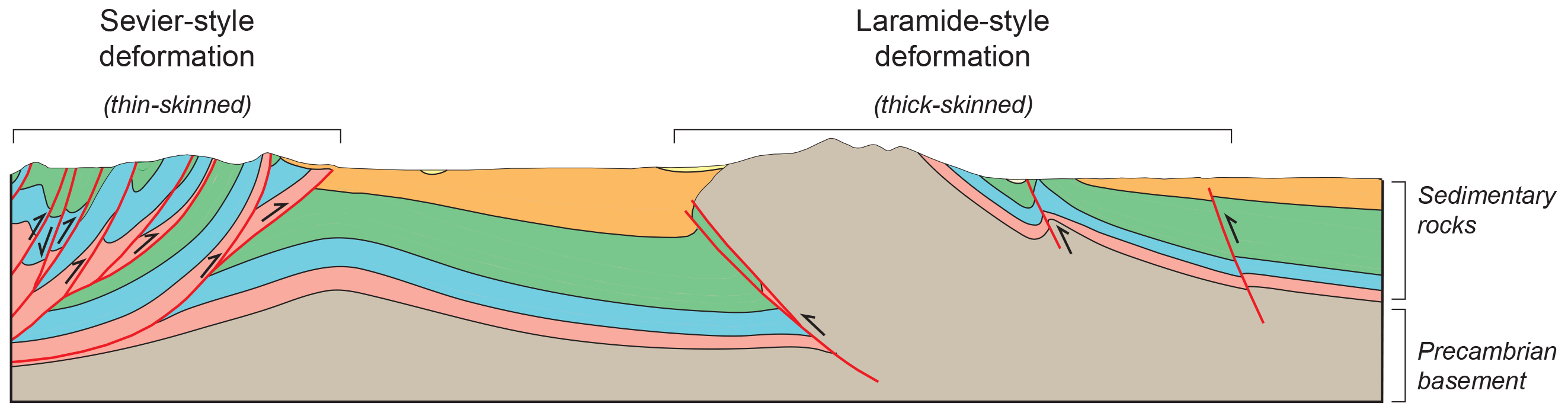

Deformational Styles

The cross section below highlights the difference between Sevier-style and Laramide deformation. Sevier-style thrust faulting is confined to sedimentary rocks above the Precambrian basement (i.e. thin-skinned).

Laramide structures offset Precambrian basement rocks (i.e. thick-skinned).

- ►References

-

Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1988, Traveler’s guide to the geology of Wyoming (2nd edition): Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Bulletin 67, 130 p., 13 pls.

Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1971, Traveler’s guide to the geology of Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Bulletin 55, 90 p.

Glass, G.B., and Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1999, Geology of Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Information Pamphlet 2, 12 p.

Snoke, A.W., Steidtmann, J.R., and Roberts, S.M. (eds.), 1993, Geology of Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Memoir 5, vols. 1-2.

Contact:

Colby Schwaderer, colby.schwaderer@wyo.gov